IDENTIFYING YOUR GARDEN PROBLEMS

It’s a Major Step in “Integrated Pest Management”

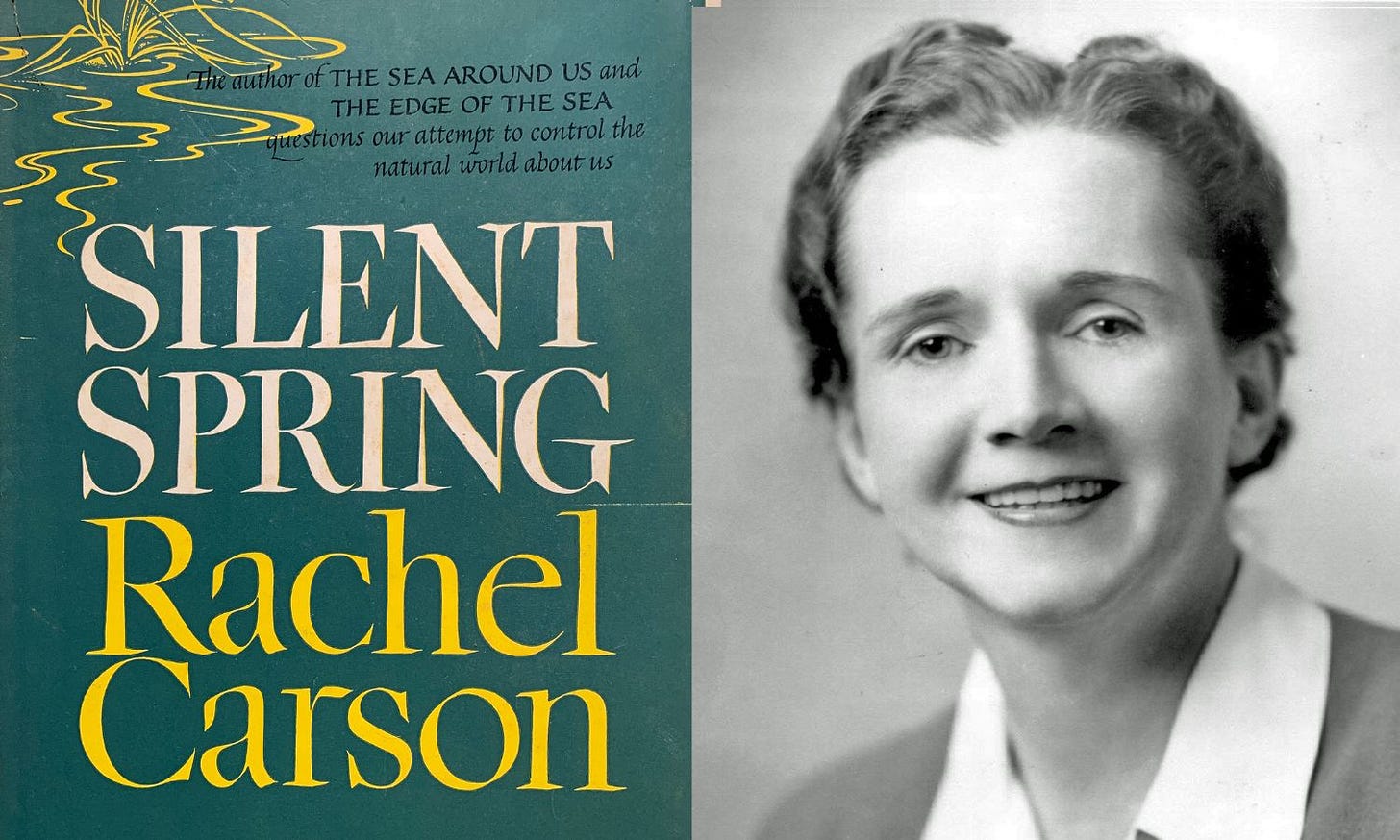

Years ago, scientists from several disciplines involved in pest management started developing something called “integrated pest management” (IPM for short) for agricultural crops of all kinds. Although the term “integrated control” had been around since the 50s, the basic perspective changed dramatically when Rachel Carson published her important book “Silent Spring” in 1962. From a focus on chemical “controls,” along with selected cultural practices and a dabbling of biological controls* (altogether, the “integrated control”), it evolved into a more formal strategy in the 1960s and 1970s. The negative effects of widespread synthetic pesticide use had been brought to light.

[* Biological pest management has been around since ancient times with an expansion in use pre-WW2. Post-WW2, though, brought in the “big guns” of chemical pest “warfare” and bio-control declined significantly.]

The principles of integrated pest management have since then trickled down to the home garden level to include the way we approach ornamentals in the landscape and edibles in the vegetable patch and orchard.

The purpose of IPM is to look at the entire system — the interrelationships of plant and environment — and THEN make informed decisions to manage (not “control”) pests. It is an approach or program that primarily focuses on preventing pest problems with an emphasis on growing healthy plants in well-planned gardens and landscapes. IPM is about using the right tool, at the right time, for the right reason.

A good IPM program includes five basic components, in this order (consider them “steps”):

Prevention

Monitoring

IDENTIFICATION

Determination of acceptable injury level

Management strategies (the last resorts)

I expect that I will kick around these five pieces separately, in some way, and maybe in more than one article for each, in the future. For now, I’d like to offer up some thoughts and guidelines on the subject of (pest) identification.

But first, a relevant story. During my first retail nursery job (1972?), I had this kind of exchange with a customer:

Customer: “I have something eating my garden plants.” [No, she didn’t tell me what plants, specifically. And even if she had, I certainly wouldn’t remember. Nor, it turned out, was it pertinent at the time.]

Me: “Oh dear,” [which I’m sure I said,] “what plants, what kind of pest, what did it/they look like?]

Customer: (with just a hint of anger for her situation but mostly matter-of-factly) “I don’t know and I don’t care. Just give me something to kill everything.”

Yes, true story. And that same conversation would be repeated many times, in many subtly different ways, over the several years I was in the retail and wholesale nursery businesses.

Although I am encouraged by a growing awareness of the consequences of using pesticides (including “organic” and “homemade” pesticides), I still hear the same lamenting and requests for silver bullets on social media.

And my answer, now more refined from trying to offer a 15-minute lecture on “knowing your pests” to a retail customer, is “The most effective way to solve the problem is to know exactly what the problem is,” or something maybe less philosophically pretentious.

Many years after my first such conversation at the retail nursery, I saw an ad running on tv for quite some time. It started with an animated version of “bugs” in the garden. The bugs, in variety, had huge eyes and even bigger teeth (long, pointed, and monster-like), and they monstrously tore apart everything in the garden. Out comes a can of spray, a quick application, and voilà, annihilation. The closing pronouncement, and I quote verbatim: “It kills everything.” With the appropriate X’s over the bugs’ huge eyes. I let out a soft sigh, confirming my concern for the world. The idea, the practice, the mentality continue.

So, let’s try to break down what that “everything” is. Or isn’t.

IDENTIFICATION

John Dewey (philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer; from ‘Logic: Theory of Inquiry’, 1938) said “A problem well put is half solved.” Indeed.

Firstly, once found, do not automatically assume that buggy things are “pests.” And don’t think that every little leaf spot in the garden is “insidious creeping rot” or the “apocalypse virus.”

Turns out, most insects in the garden are not pests. Less than 3 percent of the critters in your yard or landscape are considered pests by professionals (and I don’t mean the guys who go house to house to sell you the service of spraying “everything”). And most of those would probably not be categorized as “serious” pests (your idea of serious and another’s idea of serious is another subject).

That means that over 97 percent of insect species are harmless and maybe even beneficial. Could be they perform vital ecological functions such as pollination, decomposition, and maybe (often) even pest management. Overall, they’re a part of the bigger ecosystem (your yard and beyond) and it’s highly possible they’re just passing through, with no “benefit” whatsoever to your garden (sorry to say, sometimes it’s not about you). They are the grand bulk of the “everything.”

Plant “diseases” are even more difficult to stamp with a black-and-white label of evilness.

Plants invariably get spots, bruises, white marks, yellowing, and more physiological boo-boos. Many of these physiological issues are called non-pathogenic, or abiotic, diseases. They look like diseases (those caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes) but they do not have any causal organism that would respond to a bactericide, fungicide, or other potent product.

Not surprisingly, many such “diseases” are caused by overwatering, which more accurately, should be called overly-frequent watering. Signs of overwatering can vary. Sometimes it begins with yellowing of lower and inner leaves. Sometimes it shows itself with soft brownish tips of leaves. Sometimes it’s dramatic in the overall wilting of the plant. Although normally associated with lack of water, wilting can follow a loss in root system and too much water at the roots usually leads to roots succumbing to oxygen deprivation. Any damage to the roots or stems, be it from animal, shovel, toxin, or even particularly low temperatures, will lead to wilt.

In addition to overwatering, sometimes it’s simply a matter of old leaves (usually at the bottom of the plant or at the basal end — inside ─ of branches) yellowing, dying and falling off. Similar symptoms occur with indoor plants that have been introduced to the house from a vastly different environment (usually a humidity-controlled, temperature-controlled, air circulation controlled, water-controlled greenhouse). In the latter case, such plants need to adjust to the new environments and to do so they shed their leaves that were adapted to a different set of conditions.

When typical shade plants are grown in the shade where they belong, they produce a thin cuticle (waxy leaf coating). When these same plants are grown in bright light from the beginning of their lives, they produce thicker cuticles to protect them from the intense light. When a plant that has been grown in the shade for a while is transplanted to a location with more sunlight, however, the leaves with thin cuticles will burn regardless of the plant’s natural sun tolerance.

There are many other blemishes that are mistaken for diseases. Herbicide damage, from simply accidentally spraying to the mysteries of drift, ranks up there on the list and is becoming more common.

Leaves are also damaged in many other ways that one might think is disease or pest damage. There’s the physical damage caused by hail, wind, unseasonable sun/heat, and fertilizer “burn.”

The latter, the “burn,” is an excess of fertilizer that has been manufactured in a form that produces salts. These fertilizer salts ordinarily break apart under appropriate conditions but too many variables often prevent such splitting. Salts from fertilizers as well as some manures dehydrate roots and when dissolved are taken up by the plant to be concentrated at the tips of the leaves where they have no place else to go. It’s at the tips where they do most of their dehydrating work

Both fertilizers and manures can also cause damage with inherent ammonia. Ammonia can lead to various types of injury, including necrosis, growth reduction, and growth stimulation with increased frost sensitivity. Leaves can exhibit yellowing between the veins, looking very much like certain nutrient deficiencies. This loss of green can progress into scattered brown (necrotic) spots. The edges of leaves may curl upward or downward. Root growth is impeded and root tips may die, which leads to wilting and becomes an entry point for root diseases.

At the opposite end of this issue, there is nutrient deficiency whereby the plant isn’t getting one or more nutrients from the soil. Whatever the cause of the deficiency (there are many and believe it or not, overwatering can be the cause, there are manifest symptoms that have led many to thinking it’s some “disease.” The primary conspicuous symptom, some form of discoloration in the leaf, is called “chlorosis” (derived from the Greek khloros meaning greenish-yellow, pale green, pale, pallid, or fresh; these meanings are pretty descriptive; except the “fresh” — I’m not sure how that one connects).

Diagnosing nutrient deficiencies is iffy at best. Although many academic resources, both in print and on-line, offer illustrated comparisons of chlorosis and how it manifests itself in leaves, nutrient deficiencies are quite complex and determining the exact cause is best left to the experts who run tests to confirm suspicions. The signs can vary considerably from species to species and from season to season. They can be atypical due to multiple deficiencies and some can look very similar.

In addition to chlorotic yellowing, nutrient deficiency can show itself in other ways including with reduced or stunted growth, less flowers, and less fruit. Regardless of diagnosis, fixing a nutrient deficiency isn’t a matter of spraying with a fungicide (nor applying fertilizer from a bag, bottle, or box. Do not get on that treadmill.) Instead, take a harder look at better ways to manage the soil and feed the edaphon.

As already mentioned, “chlorosis” doesn’t always mean a lack of nutrients in the soil. Sometimes it’s because of physical plant/root/stem damage and even though nutrients of many kinds can be in the soil, the plant is incapable of taking them in.

If it’s any consolation, abiotic damage does not necessarily spread from plant to plant over time. Biotic diseases, true diseases, can spread throughout one plant and may also spread to neighboring plants of the same species or related species. With that being said, any plant struggling with an “abiotic disease” is usually in the same soil, same environment as the plants next to it, hence all the plants are struck with the same issue. Not surprisingly, even nearby plants of an unrelated species can succumb to the same “abiotic disease.”

An important take-away message is to remember that there may be several factors, abiotic and biotic, contributing to a single plant’s health problem. A “disease” is more often abiotic than it is biotic. And most often, it’s the gardener’s fault.

A good example of a complex “disease” most often caused by or at least exacerbated by the gardener is “blossom end rot,” a curious defect on tomatoes and a few other fruiting vegetables. It’s an odd syndrome that has been blamed on, almost always wrongfully, a deficiency of soil calcium. The main symptom is, of course, a brown, dryish “rot” at the blossom end of developing fruit. Only recently has science figured out at least part of the mechanics behind this issue and as of now, it seems to be a localized deficiency of calcium in the fruit initiated by water stress such as frequent, shallow watering, fluctuating moisture levels, and/or waterlogged soil. Although calcium may be present in the soil, which it usually is, it can’t reach the fruit.

Disease issues are often complex, often involving one or more fungi, bacteria, and/or virus and commonly with a background of stress-induced abiotic issues and symptoms. And then there’s the plant issues that are simply idiopathic (“id·i·o·path·ic; /ˌidēəˈpaTHik/; adjective; a medical term, relating to or denoting any disease or condition that arises spontaneously or for which the cause is unknown). We like to think that it’s just a matter of time before we discover those complex organisms or partnerships and the interactions behind them.

Secondly, it might, in fact, be a pest, disease, or weed but you still need to know what it is to put an effective AND SAFE (for you AND the earth) strategy in place.

Applying any pesticide when you haven’t positively identified the “pest” (or disease or weed) is, in the least, a waste of money. Before taking any action whatsoever, be it organic or otherwise, make sure you know exactly what the issue is. So “let’s put the problem well.”

Take a close look at the bug, the possible disease spot, the weed. Two different pests — whether insect, mite, pest, or weed — may look alike to you but may require entirely different management strategies to deal with them. And just because you see a pest-like thing on a plant doesn’t mean it’s done any of the damage you might be seeing; watch it, if you can, for a bit to see if it’s in the process of chomping (or sucking or rasping or poking eggs into the leaf or branch) or just hanging out. Take a photo, share it, ask about it. As the great contemporary Latin philosopher Lorenzo Pietro Berra once said, “You can see a lot just by looking.”

If you’ve been using simple monitoring strategies, such as yellow sticky cards, you have the opportunity for looking closely at the critter.

Knowing the plant helps tremendously in identifying pests and diseases; not just the name of the plant but it’s care and potential issues and symptoms. A gardener should be familiar with the “benchmark,” that is, the healthy version. Recognizing healthy allows one to recognize distress. Also keep in mind that variegated plants naturally show various “yellowing” patterns in their leaves; that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Get a good book or two on pest, weed, and/or disease identification; there are many. Or refer to on-line websites for university cooperative extension pest management guides; there are some absolutely terrific ones. If using an “ID app,” I strongly suggest using at least two different apps to get a dependable consensus plus follow up with one of the extension websites for confirmation.

There are plenty of specific-target pest management strategies (not “pesticides”) and they are effective and safe ONLY if you know what the pest is.

Along these same lines, don’t expect one pest or one disease to jump from one species of garden plant to any other. Most pests and diseases are fairly host specific. They usually stay within a family of plants and, in some cases, within only a genus of plants. For instance, the powdery mildew fungus that shows up on roses, does not infect squash. Peach leaf curl, a fungal disease that causes odd contortions on peach and nectarine leaves, is not the culprit in the curling of plum leaves (usually caused by aphids feeding in a manner that causes the leaves to curl over them). Speaking of aphids, those that attack roses will not attack beans. The rust of roses is not the rust of hollyhocks nor is it the same as the rust of snapdragons. And on and on.

Once the problem is identified, there is another step before you run for the bottle of “Bug Bomb 357:” the Determination of acceptable injury level, the gardeners’ version of the farmer’s “Economic injury level.” But that’s another story for another day.

Bottom-line soapbox on broad-spectrum insecticides (the “something that will kill everything,” as many gardeners still request): they are unhealthy, they lead to pesticide-resistant pests, and they diminish biodiversity. Even the ever-so-popular “organic” product Neem oil comes with important cautions.

.

Pick up a copy of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring.” And you might as well get a copy of “Since Silent Spring” by Frank Graham Jr. This latter book was published in 1970. Since Graham’s book, pesticide companies have come out with a cornucopia of so-called “safe” (mostly not) products and a “Since ‘Since Silent Spring’” is needed (although plenty of very recent books hit at the various pieces of the problem with pesticides).

.

.

© Copyright Joe Seals, 2025

Thanks for this Joe, so much knowledge and good sense as always.

The 'pest' story I like to tell is when a lady came up to me at an event and asked me how she could get rid of the terrible, evil bugs all over her plants. Luckily she had a photo with her - and, yes, it turns out they were all ladybird larvae :).

Brilliantly put. Something like this should be required reading before purchasing 'icides.