HOW TO PLANT A TREE

The VERY Complete Step-by-Step Strategy to One of the Most Common Garden Practices

Since I’ve started this Substack series, I’ve been hesitant to post an article such as this. Afterall, a gazillion articles have already been written on this very same subject and by a gazillion “tree-planting experts,” from all levels of amateur planters, professional planters, and university researchers. They all have a say and a methodology. It’s a take-your-pick buffet. [I particularly like the illustrations that almost comically offer up the itemized details on “How to Kill a Tree” based on improper planting techniques.] But I suppose it doesn’t hurt to offer another take, another layer(s) of information (much of it new), and another reminder to the latest generation of gardening newbies without being a TL:DR kind of piece. Here’s hoping my take leads to more successfully-planted trees that will fill this world that is so desperately in need of more trees.

Everyone knows how to plant a tree. You dig a hole, you put the tree in the hole, and you fill in the hole with something. I’ve often told this to my students, semi-jokingly of course. I’ve gotten by with actually following this hole-tree-fill procedure many times, either because I “knew” what I was doing or because I was admittedly lazy at the time. It does work with some species, when they’re young, when the weather is right, etc. (all part of the “know”). While other times I’ve failed (mostly the “lazy”). And I’ve seen too many other gardeners fail.

It usually does take a bit more than digging a hole, etc., of course. Most gardeners already practice beyond this semi-joke, fortunately. I’d like to build on that and add the nuances, the “tricks,” maybe the forgotten, and, most importantly and as I always do with “my take,” the new science.

This very common and seemingly simple practice has had its share of evolution, some controversy, and many knock-over-the-head revelations in the past fifty years. That fifty years is the amount of time I’ve been planting trees (and bulbs and vines and petunias and more) in my gardens, my clients’ gardens, and for various landscapers and nurseries. At the near beginning of those fifty years there was the college horticulture program that “straightened it all out” for me. And then dozens of other inputs, for the decades after college, unstraightened it and re-straightened it once again. But a different straight. Almost all because of new scientific discoveries (and THAT is the way science works!)..

These are the steps in planting bare-root, B&B, and containerized trees. This planting methodology is also appropriate to almost all shrubs.

The Pre-steps

Get a good handle on any weed issue before planting.

If you’re planting into a lawn — not a good idea unless you live where summer rains water trees and grass naturally and you’ve chosen a tree that does well surrounded by grass — remove the grass within the area defined by a circle three feet out from where the trunk of the tree will be.

Do you need to call 8-1-1 (for large trees requiring large holes)?

Have your holes ready. Before going nursery shopping, before moving a plant from one place to another, or while you’re waiting for your mail-order shipment, have the hole(s) ready (at least partially ready). See Step 1. below for further details. At this point, while you’re digging these “preliminary” holes, remove the big rocks (not the little ones) that get in your way and take up too much space in the hole; if you remove so many large rocks that it equals a substantial portion of the hole space, you’ll have to replace them with soil from elsewhere (preferably your own property and not from a bag). Similarly, remove large logs, old boots, and other waste. Break up larger, hard soil clods.

If for some reason you end up with a plant, especially a bare-root plant, in your hand and you’re not sure where to plant it or there is some other reason it can’t go into its appropriate spot right away, it’s best to simply dig a hole (or trench for multiple plants) anywhere and plop it in. This is called “heeling in” and it is better than leaving the plant in the garage or in a bucket of water.

With container plants, especially those that are to be planted during summer heat, make sure you thoroughly soak the root-ball before planting.

If you’ve never planted on your property before or if you’ve never planted this specific small part of your larger property, dig the hole 24 hours before planting. This allows you to do a “perc” (percolation; often spelled “perk”) test.

The proper way to test for water percolation:

Dig a hole about 1 foot wide by 1 foot deep, straight-ish sides. If you’re testing your entire property, dig several holes scattered around your yard, since drainage can vary.

Fill the hole with water, as quickly as you can, and let it drain completely. This saturates the soil and helps give a more accurate test reading. No need to time it this first time.

Refill the hole with water.

Measure the water level by laying a stick, pipe, or other straight edge across the top of the hole, then use a tape measure or yardstick to determine the water level.

Continue to measure the water level every hour until the hole is empty, noting the number of inches the water level drops per hour.

The ideal soil drainage is around 2 inches per hour, with readings between 1 inch and 3 inches generally acceptable for garden plants that have average drainage needs. If drainage is more than 4 inches per hour, it might be too fast for the plant species. If the rate is less than 1 inch per hour, your drainage is too slow, and you’ll need to improve drainage or choose plants tolerant of wet soil; it may be time to think about serious drainage engineering (e.g., French drains, vertical chimney drains, etc.). Just a reminder: “amending” the soil doesn’t fix poorly drained soil; in fact, it usually exacerbates the issues.

.

Start planting…

Step 1.

This should be an extension of a “Pre-Step — Have your holes ready.” If you’ve done that, with this Step you’ll be adjusting the already-dug hole to fit the root-ball/container you have in your hand. Otherwise…

Dig a shallow, broad planting hole. The hole should be at least twice as wide as the existing root spread and only a smidge deeper (#1 on the main illustration below). Should a thorough root washing (see Step 3b., in text below) be necessary for a container plant, the root system/spread will be even greater than what’s visible unwashed.

The sides of the hole do not need to be straight down. In fact, a subtle slope inward to the bottom is preferable; as long as you leave the bottom of the hole flat enough and large enough to support the bottom of the root-ball.

Square hole? This has been proposed by a handful of professionals and non-professionals, but the science shows that it is no better at encouraging tree roots, no better at preventing a rootbound condition, and it’s more timely to dig with more soil to be removed from the hole than a circle with equal width.

In compacted or otherwise hard soils, make the hole as much as three times as wide as the diameter of the root-ball of the plant but only slightly deeper than the root-ball. It is important to make the hole wide because most of the new roots on an establishing plant are lateral growing and they must push through surrounding soil.

Digging the hole only slightly deeper minimizes settling; settling is not a good thing — it can lead to the flare of the tree (see below) eventually being covered by soil.

In clay soils where a shovel may have created slick sides, scratch the floor and walls of the hole to create a roughly textured surface that allows roots to “grab” it better.

Break up and clean the removed soil. Remove sticks, large stones, and oddball inorganic material. Breaking up the soil in a large area provides newly emerging roots room to easily expand into loose soil without obstructions.

The roots or root-ball should sit on firm soil.

Before moving on to the next step, fill the hole with water and let it drain. Then wait a day before actually planting.

.

Step 2.

Before placing the tree in the hole, double-check to see that the hole has been dug to the proper depth. If the tree or other plant is planted too deeply, new roots will have difficulty developing due to a lack of oxygen and the bark of the trunk at the flare will slowly rot, causing a long-drawn-out decline in the tree’s health.

Identify the trunk “flare” (“arch” or “crown”). (#2 on illustration above). The trunk flare is where the roots begin to spread at the base of the tree. Sometimes it’s subtle, sometimes obvious. This point — the flare — must be mostly visible, with no part buried, after the tree has been planted. The tree trunk shouldn’t look like a sunken telephone pole.

If the trunk flare is not visible in the nursery can, you may have to brush away some loose soil from the top of the root-ball. Check this at the garden center. One often mentioned planting instruction is the advice to “plant at the level it was in the container;” but as just noted, the flare may not be uncovered in the container due to soil being washed up on it.

There is no conspicuous “flare” on smaller shrubs. But there is often a “crown,” even in dormant plants, where multiple stems (or remnants of such) rise from the soil. With most of these plants, it’s a matter of finessing the setting of the plant so the crown is exactly level with the final soil surface, with a bit of it probably below the surface and a bit of it probably above the surface.

To check for proper depth, slip the plant, pot and all, down into the hole. Use a taught string line or straight garden tool handle to “mark” the finish grade as your guideline (shown below). Line up the flare — not the top of the pot — slightly above the native grade. Dig the hole deeper, if need be, or replace some of the soil to raise the bottom of the hole. (See #2, #2+, and #4 in illustration at Step 1.)

Symptoms of trees planted too deeply (“flare” covered) in the soil include:

reduced growth rate and generally lack of vigor;

smaller leaf size and/or defoliation; yellowing (almost always mistaken for nutrient deficiency);

late spring leaf emergence (for deciduous trees, or other times for evergreen trees);

some new growth may develop each spring, only to die-off come summer;

fall coloration and leaf drop comes early;

bark splitting;

wrapping, girdling roots;

branch dieback; and eventually, usually after a few seasons, …

TREE DEATH. Because death occurs after such a long period, tree owners don’t associate the decline of a tree with how it was planted. By the time damage s noticed, it is often too late to fix.

.

Step 3.

Slip the tree or shrub out of the container gently.

If planting a small container plant — 1-gallon size maybe up to 5-gallon size — it usually works to tip the plant and container over and tap the edge of the container downwards, gently against a hard, raised surface, with the root-ball given space to slide downward and out. If you can, hold your palm flat against the top of the root-ball with your fingers splayed to fit around the stem(s) of the plant to hold the root-ball together. You may have to use a stiff long knife to cut between the root-ball and the inside of the container to reduce its connection to the container.

For heavier or unwieldy containers, don’t tip the plant over; instead, use a blunt tool to tap just the edges of the container (not the root-ball) down from the root-ball.

When planting a balled-and-burlap tree or shrub, remove the twine and burlap wrapping completely. Handle the ball with care, do not drop it, step on it or otherwise abuse it. Inspect the ball to make sure that there is not another layer of twine wrapped against the trunk, which is often the case in larger root-balls. If so, remove this twine. Look at the soil against the trunk — field grown trees and shrubs are grown on level land. A root-ball is round. Soil is most often pushed up against the trunk to make the root-ball stable. This soil must be removed. Gently brush away the soil that is against the trunk until you see just the beginning of the top of the first root. Do not scrape the bark.

.

Step 3b. (optional)

Many plants are often sold way past their version of an expiration “planting date,” wherein they have been in the container for too long and their roots have begun to wind around each other. Sometimes this is quite obvious, with a knotted tangle of roots showing about the soil surface in the pot. At other times, the tree or plant you buy may not appear root bound, but inside the soil ball there exists an old root-bound clump of circulating roots, virtually invisible within a “shell” of recently added potting soil. Plants with dense, tangled root systems should be rejected at the nursery or returned when discovered later. But sometimes they do find their way to a garden. Then what?

Maybe the best way to find if this is a potential future issue and/or to fix such an issue is a practice called “root washing.” It can help correct circling and girdling woody roots and it’s also a good way to find the root crown for the most accurate planting at grade.

Research on “root washing” is still limited, however. It has advantages but it also has limitations and potentially serious drawbacks. This method has some value with deciduous plants when they are dormant (for most areas of North America, this means after deciduous plants have dropped their leaves in late fall). But this is not to be considered standard practice for planting things. If a root problem is a serious suspect, root washing might be worth considering as an option.

In which case, you’ll need to wash all or most of the soil off the roots so that you can see existing problems. Root washing allows identification of the first primary roots so the correct planting depth can be determined. With no expansive root-ball to displace soil (which would otherwise be thrown somewhere else), it mostly eliminates the need for staking. If there is a problem, you can fix it before planting the tree.

Soaking the roots overnight or longer in water loosens the nursery soil and usually allows for easy soil removal with a gentle spray from a garden hose. A wheelbarrow or plastic drum works well for this step so you can dump excess water. When you wash the soil from the roots, work in a cool, shaded area with access to water. Once root washing begins, the roots will need to be kept constantly moist. Gently shake off as much media as you can.

If there is a serious problem, you can fix it before planting the tree or shrub. Remove any dead, damaged, mushy, or circling roots. Other things to look for when inspecting root systems are knotted roots, J-hooked roots (roots that make a sudden turn, creating a J-shape), and other such deformities.

While the roots probably will be fewer and shorter and will take longer to develop, they will be able to grow into the soil of the planting location.

The process does damage the roots, making it even more critical to water the tree well for the first year. It is also very important to keep it mulched to keep the roots cool and prevents loss of water from the soil.

It’s a good idea to root wash any plants brought in from a non-certified nursery and in actual soil. That includes evergreens/conifers.

.

Step 4.

Place the tree at the proper height with the trunk flare above the finish level (#4 in the main illustration at Step 1). The whole root-ball should, in fact, be planted a little higher than the finish grade, maybe ½ inch and up to 2 inches above the finish grade. This raised height will also allow for some predictable settling over time, with the largest, heaviest trees settling the most and requiring the higher measurement above grade. To avoid damage when setting the tree in the hole, always lift the tree by the root-ball and never by the trunk.

Straighten the tree in the hole. Before backfilling, it often helps to have one person hold the tree, especially with larger, weightier trees, while another person — YOU — views it from several directions to confirm the tree is straight and above finish grade. Once backfilling starts, it is tricky, if not difficult, to reposition the tree.

Spread the roots as horizontally as possible, without having to force them. Create a network of roots to catch the widest pool of water. The first and most vigorous roots to grow are the lateral roots, the ones that will best anchor the tree and will take in the greatest volume of water and nutrients. That happens even if the tree is a “tap-rooted” species.

If you are planting a bare-root plant, place a conical mound of soil, shaped to fit into the cavity between the roots of the plant, at the bottom of the hole.

.

Step 5.

Fill the hole. (#5 on main illustration at Step 1.)

If necessary (especially for totally bare-root plants or seriously root-washed plants), form a cone of soil in the center of the hole to support the root crown of the tree, and arrange the roots radially, spreading them out as evenly as possible over the mound.

Backfill with native soil. Do not use any amendment or any type of “soil mix.” Start by filling about one quarter to one third full and then water before filling further. Be careful not to damage the trunk or roots in the process. Don’t stomp on the soil with your feet or with heavy tools or equipment. Especially don’t push on the root-ball itself. Fill another one quarter to one third, watering as you go by pushing the end of the hose as a “probe” into the soil to completely “muddy” it (landscapers call this process “muddying”), taking care to eliminate air pockets that can cause roots to dry out in the future.

Water to settle the completely filled hole well. Don’t skimp on the water. This will be the last time you will be able to provide really good deep soakings that will push out dry air pockets and create a deep reservoir. Regular moisture is critical to survival after planting, so the soil should not dry out more than 1 inch deep on the surface before watering again.

To reiterate: during this process, no amendment has been added to the soil. None is needed, regardless of your soil conditions. This is contrary to nearly universal (but improper) practice but it is the correct way to ensure long-term success of the tree or other plant. The reasoning behind this new practice is spelled out in one of my earliest articles, “THE BIGGEST* GARDENING MYTH.”

Also, do not add fertilizer immediately after planting. Generally speaking, the best time to “fertilize” landscape plants— IF AT ALL — is when their roots have become established and they begin to grow actively. And ONLY if the surrounding garden clearly shows signs of identifiable nutrient deficiency.

If organic fertilizers are involved, there will be a lag time before the material is available to the plant. Speaking of which, if “organic” is the mindset, it’s time to consider composting, mulching/topdressing, cover crops, and putting roots in the ground as the best way to build a soil that supports plants appropriately.

Nor should you add vitamin B1 (thiamine) products; they do not “prevent transplant shock” nor “stimulate new root growth” when transplanting or planting trees, shrubs, roses, or any other plants. Nor any other such “root starter/enhancer/etc.” product.

.

Step 6.

Remove any existing nursery stake(s) and its ties. These stakes, almost always tied very tightly to the tree with snugly wrapped nursery tape, are placed at the nursery to allow more plants to be grown in a smaller space, to make the trees easier to handle when they must be moved, and to help keep it intact during shipment. They are not useful in providing proper support once in a garden setting.

One of the biggest changes in tree planting has been the way we stake trees. Or, now more fittingly, “how we stake root-balls.” A few trees may actually need stakes to hold up their trunks when planted but the more important matter is to hold the root-ball tightly in place while it tries to put roots into the native soil.

If planted and watered in well, the root-ball will fit snugly enough to the native soil to anchor the tree securely while the tree begins to develop. However, if the tree still wobbles in the hole too easily after planting, there may be a need for temporary, loose anchoring. The wobbling may have happened because the root system was minimal or because severe root pruning was done to correct tangling. The more common reasons why root-balls become wobbly are because the backfill wasn’t settled enough by watering or an organic “amendment” was used.

If the plant is a bare-root or if you’ve washed the roots and filled the hole properly thereafter, the need for staking will be almost entirely eliminated.

For planting large trees, the ideal solution to keeping root-balls steady until the roots grab deeply into the soil is to use “root-ball anchors.” Commercial versions involve hardware used to wrap around and hold down just the root-ball, often involving boards or sturdy straps that cross over the top of the root-ball and are held down with cabling beneath the soil. Nothing is tied to or otherwise attached to the tree.

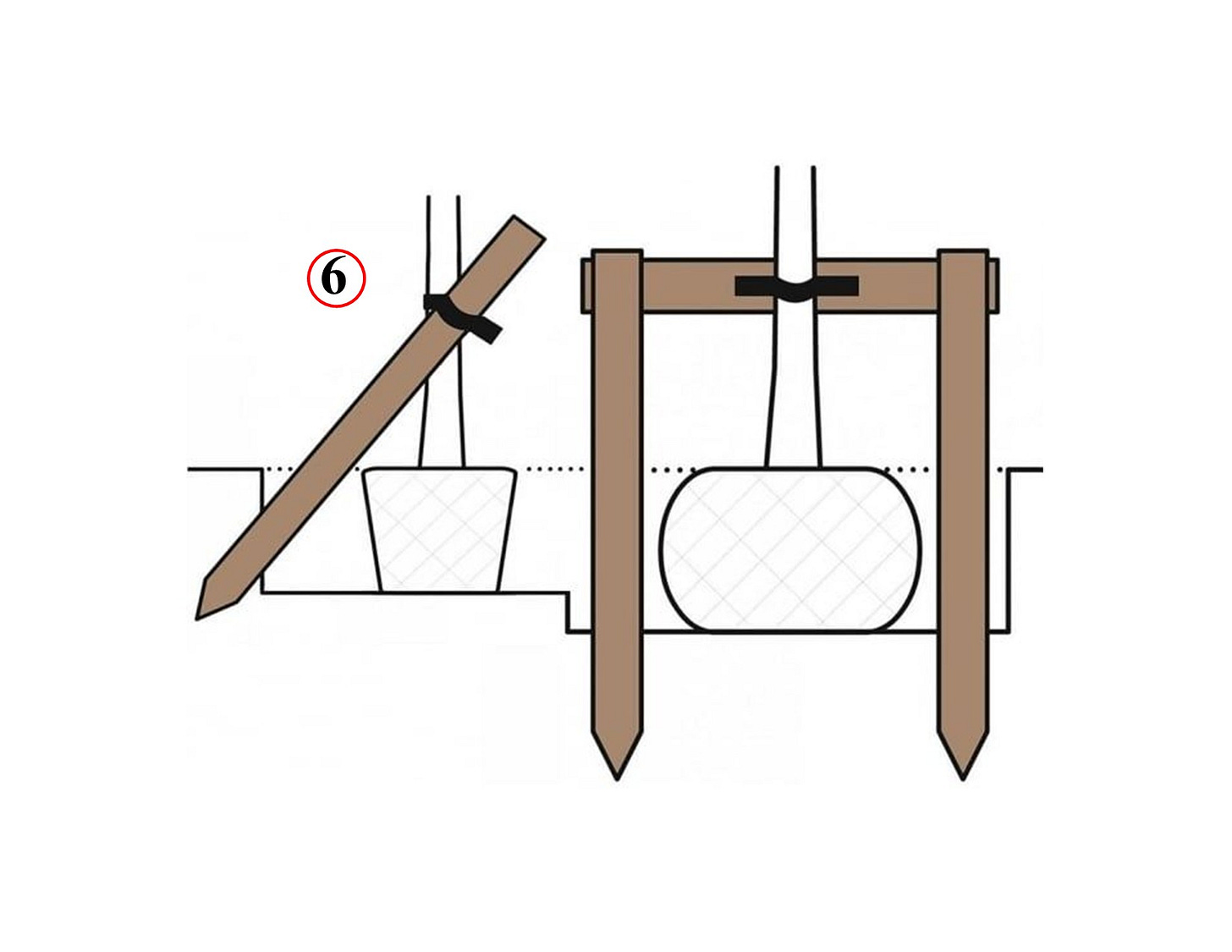

A simpler root-ball anchor is a short stake set at a slight angle, starting against the trunk at just above the root-ball, and pounded down at an angle into the side of the hole. It is tied loosely at the trunk; shown in the illustration below, #6, left. With larger root-balls, stake the tree low with a framework of short, sturdy stakes and a crossbar, with the tree tied to the crossbar; shown, #6, right.

Or, in the rare instance when the tree itself bends over soon after you remove the nursery stake, use new tall stakes (tall enough to pound 18 to 24 inches into the ground with enough extra to reach to the branches of the actual crown (not low spindly branches).

Use two stakes set on opposite sides of the tree and pounded into the native soil (NOT the root-ball) if the tree is single-trunked and small. If you have a large tree, a naturally low-branching tree, or a multiple-trunked tree, use three stakes. Do not leave the stakes in place for longer than 12 to 18 months.

With this kind of tall staking, use wide, strong but flexible tying material to secure the tree to the stake; it will provide necessary “sway” and minimize injury to the trunk. Make a figure eight between tree and stake and fasten the tie to the stake with a good knot and maybe a nail or staple. The “swaying” allows the trunk (“bole”) to develop “laminae” befitting the stresses. Laminae are layers of tissue (as in “laminate”) that form just beneath the bark. Each of these specialized lamina is a fiber-reinforced composite (composed of naturally strong cellulose microfibrils). These fibers are substantially (up to 40 times) stiffer than the other materials of the wood. Think a laminated beam for a house ceiling.

Weak trees can snap when stakes are too close, inflexible, or if the tree is simply overgrown.

Most problems with staking incorrectly come from ties becoming too tight or from damage after storms. Check the ties regularly for rubbing and adjust if necessary. Constriction of the stem by ties happens very quickly, so fast growing trees need frequent checking. After bad weather, check for abrasion and snapped stakes or ties replace stakes whenever they fail.

Upon growing enough roots to anchor itself into the ground, a plant is said to be “established.” You’ll see the phrase “once established” in plenty of books and magazine articles. This allows a plant to become more independent, primarily in terms of water needs.

No need to stake anything but trees, lofty shrubs, and other plants of extreme vertical emphasis that may have their root-balls wiggled by the wind.

If wind is a determining factor in the choice of a landscape tree, make sure you plant a tree that is wind resistant or can be trained easily to be wind resistant. Even wind-resistant trees sometimes need staking to help their roots become the anchor.

Other tips for success with planting trees on windy sites:

Shy away from traditional “lollipop” trees (species with the single, skinny trunk with a rounded crown). Instead, choose trees that are naturally multi-trunked.

Don’t plant overgrown, tall, lanky specimens. Always better to start with smaller

specimens than with bigger ones.

Plant trees in groves. There’s a “rule” about planting trees a certain distance apart to allow their crowns to spread — that’s a myth, too. The individual trees within groves of single species (nature does a lot of this) adapt to each other and fill a particular niche as one. They do not compete with each other. This does not apply to plantings of mixed species.

Choose trees that naturally take on windswept habits. This includes pines and cypress. Their sweeping with the wind is their way of adjusting without snapping.

Be liberal in the pruning process (not in the first year). Carve big holes through the tree’s canopy to

allow the wind to flow through rather than ask the tree to resist — and when the tree must resist, the wind almost always wins.

.

Step 7.

Build a berm. A berm is a raised circular edging, four to six inches high, which creates a basin set just outside (two to three inches for trees, less for smaller plants) the edge of the root-ball. Sometimes called a “donut dam.” (#7 on main illustration at Step 1.)

Unlike dug basins, berms can be knocked down if incessant rains lead to long-standing saturation.

Keep the berm for at least the first year, increasing the diameter of the ring every couple of months or so.

.

Step 8.

Water. AGAIN. Soak the tree using the berm; fill it up, let it drain, and fill it up again. In clay soils, let the hose run slowly. In sandy soils, let the hose run so much that it fills the berm area quickly without blasting a hole in the soil.

Wait until the soil surface dries completely (down one to three inches, depending on the size of the tree, even less for smaller plants), before watering again. Water the tree for the next three years adjusting the location of the water according to annual root growth.

.

Step 9.

Place a mulch on the soil above the tree’s root-ball. The mulch, more than anything, provides food for the all-important edaphon, including the all-important mycorrhizal fungi. Mulching with homemade compost, especially, provides superfood for the soil biome as well as plant growth hormones. Second to homemade compost, wood chips can be used for large trees and are incredible at helping the mycorrhizae grow and connect. A mulch also acts as a blanket to hold moisture and reduce competition from weeds. All of this is critical to the growth of a new tree. (See #9 in main illustration at Step 1.)

A two- to four-inch thick layer is ideal at this time; the smaller the tree and/or the less weed competition, the lesser depth. When placing mulching material, keep it away from the actual trunk of the tree or plant.

Keep a mulch-free area, two to four inches out from the base of the tree, to avoid moist bark conditions. (See #9+ in main illustration at Step 1.) Mulching material against the trunk often causes decay of the living bark at the base of the tree. Especially do not create a “mulch volcano” up against the trunk.

The mulch will almost always gradually float back against the tree trunk with each watering. Simply push it back into place or devise an inner collar (e.g., a plastic nursery container with the bottom cut out and a slit up one side to get it around the base of the tree).

.

Step 10.

No real need to prune at or after planting, at least not a lot. Do cleanly remove dead branches, broken branches, and branches that are rubbing to the point of becoming damaged, only.

Do not top newly planted trees, do not “tip back” branches, and do not “limb up” (remove lower lateral branches) the trunk at this time. Pruning back the crown of a new tree in any way (the common assumption being “to compensate for any roots lost during the planting process”) throws the new tree out of whack. Deciduous trees produce auxins — special plant growth hormones — that kick a tree into growing gear at the appropriate time. These auxins are concentrated in the very tips of dormant branches of deciduous trees including those of our most popular fruit trees. Cutting off these tips removes the auxins and compromises the tree’s ability to produce appropriate new expansion. Kind of like a lobotomy on trees.

Limbing up a young tree to produce that instant “lollipop” look distresses the tree in another way. In addition to adding more photosynthetic power from their leaves, these smaller branches are necessary early on to build the trunk’s layered tissue that will help support and protect the tree. The laminae here are produced naturally where the branches join the trunk, the area called the “collar” (an important term for those who prune trees).

Wait for a full season of growth to begin necessary corrective or aesthetic pruning. This includes waiting to “train” a tree. This will give the tree another season’s worth of growth to produce a more foliagey canopy. This larger, fuller canopy will maximize the sun’s energy — through photosynthesis — to make the tree’s own food and send some of that food downwards to make more roots. More roots will help “establish” the tree. This is the most important thing that a newly-planted tree — or any plant, whether deciduous or evergreen -- needs to do to survive and succeed and it starts with the chlorophyll of the leaves. The more leaves, the more processing, the more food to be sent to the developing root system — the critical anchor for the tree, needed now, at this point, more than ever.

.

Step 11. (optional)

Tree wraps are long, thin strips of material (plastic, paper, or burlap) that are wrapped around a newly-planted tree’s trunk to protect it from various environmental threats, including the hazards of winter sunscald or summer sunburn (also, sometimes, called “sunscald”) as well as damage by larger herbivores.

Winter sunscald is caused by sudden temperature changes within the bark. On a sunny, cold winter day, cold hardy tissues in the bark on the south to southwest side of the trunk are exposed to direct sunlight and warm up. The bark warms during the day and must withstand freezing temperatures at night; unfortunately in many cases, the bark tissues are unable to reacclimate or regain cold hardiness quickly enough.

Although it has been suggested that trees under water stress are more prone to sunscald, this has never been confirmed by research. Watering during prolonged periods of drought would still be recommended to reduce the overall stress on trees.

With deciduous trees in areas of intense winter sun, avoid possible winter sunscald by using a white commercial tree wrap (an insulation to temper temperatures in addition to being a sunblock). Do not use brown paper tree wrap or black colored tree guards as they will absorb heat from the sun and they don't significantly prevent cracks from frost or sunscald.

Put the wrap on in the fall and remove it in the spring after the last frost. Wrap newly planted trees for at least two winters and thin-barked species up to five winters or more. You can also simply wait until the canopy is wide enough to provide natural shade for the trunk. Do make sure to check the wraps often to make sure they are not constricting the trunk or harboring pests.

Sunburn of the summer kind typically occurs on the side of young trees that is exposed to high light intensities, usually the south to southwest sides. Young trees with thin bark, including most fruit trees, are more prone to sunburn. Trees planted in parking lots or surrounded by pavement and buildings are especially prone. In the warmer summer areas, the practice of “mulching" with reflective rock may hold and radiate damaging heat back to the tree.

Trees grown in nurseries where close spacing provided shading of their trunks and trees grown in areas with much lower light intensities are prime candidates for sunburn when planted in gardens where light intensity is very high.

Consider placing a light-colored, upright board on the southwest side of the tree near the trunk to provide shade during the critical time of year.

Possibly the best proactive methodology for sunburn prevention is to leave the lower branches on young tree trunks for a few years after transplanting to shade the bark. This will prevent sunscald and sunburn as well as help the trunk develop strength as the tree becomes established in the landscape.

.

AFTER-PLANTING CARE

Newly-planted trees need to be watered unfailingly for a while to get off to a good start. It’s the most important thing in early tree management.

And the most important thing you need to know about watering: “water deeply and infrequently.” It’s one of my three gardening mantras. Here’s a nutshell version of the watering process for the new baby in the ground:

Wait for the surface of the soil to dry a bit. A “bit” is relative, of course. With smallest plants, a bit is a teeny-weeny bit, maybe just visibly dry. With largest trees, a “bit” just might be a finger finding dry soil when stuck into the ground up to its last knuckle.

When the soil surface is dry a “bit,” water well to soak the whole root-ball. Water thoroughly to cover the entire area of the root-ball and then some and enough water to sink down to the depth of the root-ball and then some. Fill the berm area.

Water trees for the next three years adjusting the frequency and spread of the water according to annual root growth.

.

“Ces arbres qu’il plante et à l’ombre desquels il ne s’assoira pas, il les aime pour eux-mêmes et pour ses enfants, et pour les enfants de ses enfants, sur qui s’étendront leurs rameaux.” ~~ Hyacinthe Loyson, 1866

[English translation, 1870: “These trees which he plants, and under whose shade he shall never sit, he loves them for themselves, and for the sake of his children and his children’s children, who are to sit beneath the shadow of their spreading boughs.”]

Planting a tree is a promise to all future generations.

© Copyright Joe Seals, 2025

Had my first real experience with real leaf, the nonprofit tree planting organization, some good instruction