ANOTHER ROUND OF RANDOM BITS OF "DID YOU KNOW"

Volume 5 of Oddments, Scrapings, Snippets, Fragments, and Crumbs I’ve Found about Gardening and Horticulture and Such

Otherwise, more fun stuff; this time kind of in the form of a Jeopardy question…

It’s September so let’s start with this:

What’s the birth month flower for September?

Morning glories are often associated with September, when they reach their peak bloom in some areas, and are considered one of two birth month flowers for those celebrating this month. It symbolizes tenacity and tenderness and encourages the September-born to pursue their dreams with perseverance and temperate strength.

Morning glories have long been a symbol of love, both undying and unrequited. They also symbolize enlightenment, resilience, and the power of rejuvenation. On the downside, it represents the transient nature of life.

In Japanese culture, the morning glory signifies fleeting beauty. In Japanese lore, the morning glory flower was associated with the story of Izanagi and Izanami, the god and goddess of creation. The flower was said to have grown where Izanami was buried and symbolized her love and beauty. Asagao, as it’s known in Japan, is considered a symbol of good luck and prosperity especially if you dream of its flower. The flower, itself, represents love, affection, and gratitude.

To some Indigenous Americans, it is a symbol of strength and resilience, while in other Native American cultures, it’s believed to protect against evil spirits and bad luck. In Aztec mythology, the morning glory is linked to sacrifice and penance. The Maya believed the morning glory plant possessed a spirit that allowed direct communication with the gods (usually via the hallucinogenic seeds).

Oh yeah, aster, too, is a birth month flower for September.

From whence came saffron?

It is thought that the domesticated saffron crocus most likely arose as a result of centuries of systematic selection from the wild Crocus cartwrightianus in the southern portion of mainland Greece. As it is now, Crocus sativus, the plant we know as the source of saffron, is a sterile triploid and unknown in the wild. It relies upon manual vegetative/asexual propagation for its continued distribution.

Is saffron the world’s most expensive spice? Maybe yes, maybe no. Because of its low yield per plant and labor-intensive hand harvesting, it comes in at $5,000 to $10,000 per pound. On the other hand, you only need a small amount (0.15g or 3 or 4 threads) for a paella for six. There’s 454 grams in a pound and 0.15 is 3/20ths, so a tiny pinch of saffron will cost you…

Is it a Filbert or a Hazelnut?

Hazel is the common name, albeit rarely used commonly in the U.S., for plants of the genus Corylus. Corylus avellana and various hybrids (usually with the Turkish hazel, Corylus colurna) provide us with the commercially-produced nuts. Corylus avellana is commonly called the common hazel, Corylus cornuta (an American native) is the beaked hazel. Corylus cornuta var. californica, is the California hazel or Western Hazel.

The nuts, therefore, are hazelnuts. At least in English-speaking countries. So, from where did the word “filbert” come? Supposedly, “filbert” comes from St. Philibert (Philibert of Jumièges'). Although said saint is from France, St. Philibert Feast Day is celebrated on August 20, which is about when filberts (filbert nuts?) ripen in England (particularly Kent). Filbert is an English simplified spelling version of Philibert (and pronounced differently).

Although some say “filbert” is used for commercially produced nuts, two industry associations, Oregon Hazelnuts and Hazelnut Growers of Oregon like the word hazelnut, obviously. What was once the Oregon Filbert Commission is now the Oregon Hazelnut Commission. Oregon produces about 65,000 tons of hazelnuts per year, which is pretty much all of the U.S.s production (but only about 8 percent of the world’s production). Who would like a recipe for “Oregon Biscotti” (a recipe I developed last year; it has hazelnuts, of course, which grow all around me here in Corvallis, as well as dark red cherries, grown not far from here)?

The words filbert and hazelnut seem to be used interchangeably in everyday parlance and I see nothing wrong with that. I think everyone knows what the other person is talking about. I think.

Do plants move?

Plants don’t walk but they do move. By hydraulics. Oxalis corniculata (creeping wood sorrel; an ultra-nasty weed here), for instance, can quickly fold its leaflets in response to shifts in light, temperature, or touch. It does this with tiny changes in water pressure within its cells; if it’s in response to light changes, it’s called nyctinasty and if it’s because of touch, it’s seismonasty. Other plants with such talent include the familiar Mimosa pudica (Sensitive Plant), which folds its leaves dramatically when touched, Desmodium gyrans (Dancing Plant), whose leaves slowly “dance,” and Albizia julibrissin (Persian Silk Tree), a beautiful flowering tree that closes its feathery leaves at night (nyctinasty).

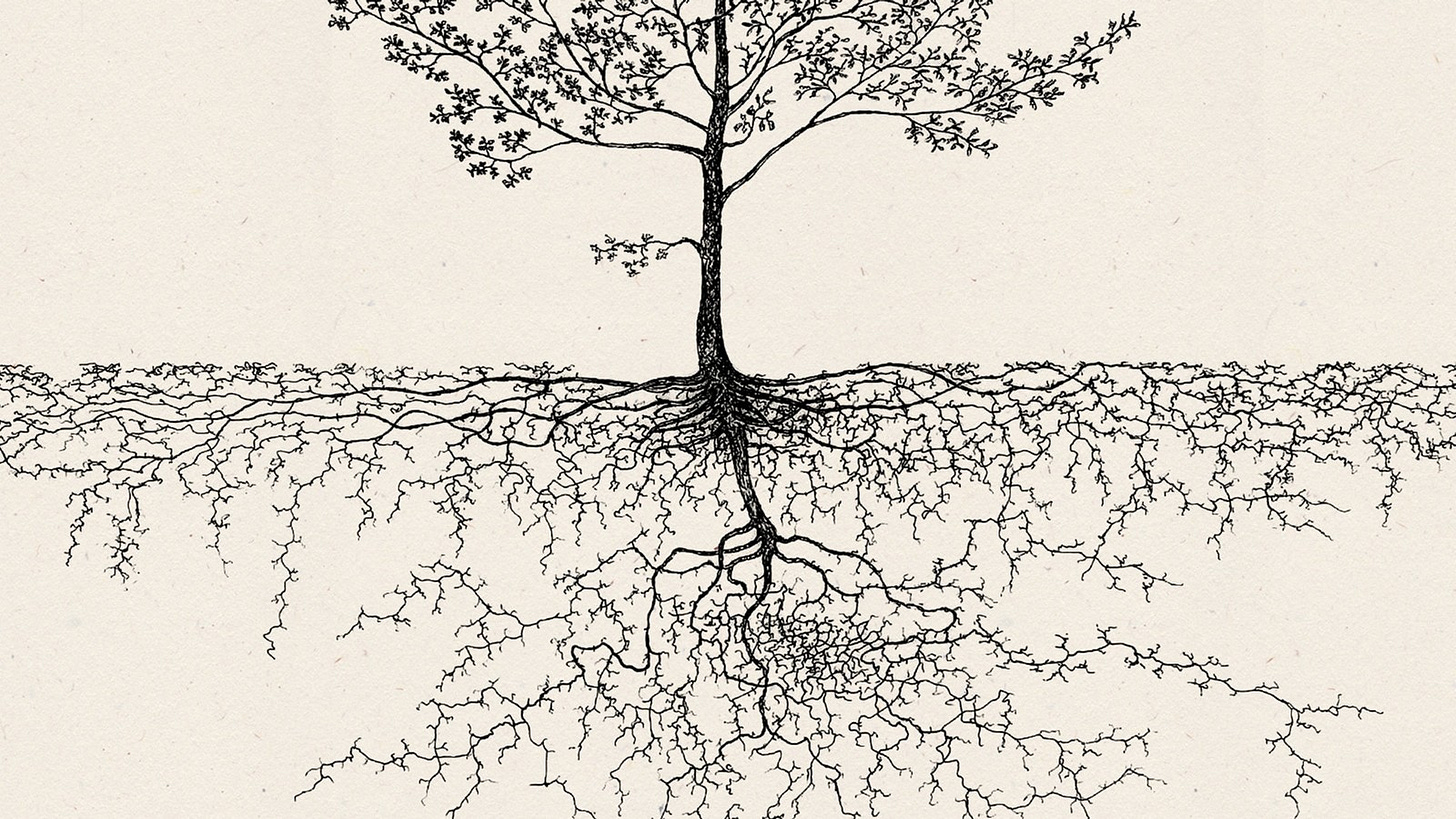

How deep do roots go?

Farther than we thought. New research reveals that many plants have a hidden second set of roots that extend far deeper into the soil than the primary set of roots. The study was published just last June in the journal Nature Communications. This second sizable network of roots extends, on average, another three feet down, which enables a plant to access deeper soil nutrients. The old assumption was that plants got most of their resources from surface soil — through rainfall or leaves falling on the ground — and had progressively less roots as they went deeper into the ground. Add to this the extensive network of mycorrhizal fungi that go far beyond the rhizosphere, in a healthy soil, and Mother Nature has the potential to feed its trees without the need for a bag of fertilizer. [Yes, the latter was seriously tongue-in-cheek.]

Where have all the giant sloths gone?

Pawpaws (Asimina triloba) have the largest fruit of any native tree. Small frugivore animals have fed on these fruits for thousands of years and currently still feed on the fruits of this tree, but the seeds they expel are dropped straight onto the ground below the tree. That’s no way to disperse the species beyond its limited territory. So how did this species spread beyond even its small, original native range? What animal was able to eat the large fruit, SEED AND ALL, and carry that seed an appreciable distance? The answer: Scientist think the now-extinct megafauna, the massive herbivores such as woolly mammoths and giant sloths, ate the fruit (and swallowed the seeds and then “dropped” the still-intact seeds elsewhere).

Are figs actually “fruits?”

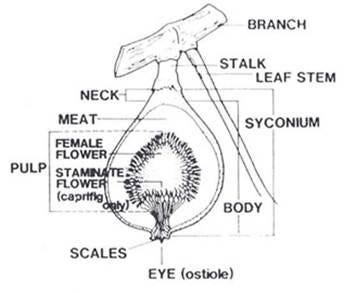

Figs (Ficus carica) are not actually fruits in the conventional sense. Botanically speaking, they are inverted flower clusters called syconia. The inside of a fig is lined with tiny flowers which are, in some types of fig (caprifigs), pollinated by specialized wasps and when those tiny flowers are pollinated, they do swell up into tiny fruits – but still not what we see as a fruit. Common figs, though, have been bred to no longer rely on such wasps; they are parthenocarpic, meaning they develop without pollination and thus without wasps.

The synconium is a pad, the pad itself being technically a receptacle that sits at the end of a peduncle (flower stem). The receptacle, with its multitude of tiny flowers, folds itself over into an oval globe, as it develops and swells, almost closing itself at the outer end, leaving just a wee bit of an opening (the ostiole).

Even when wasps are involved (as in caprifigs), you won’t get any crunchy bits when you bite into one. Figs produce an enzyme called ficin, which dissolves the wasp's body into proteins. You’ll eat the fig, and only the digested insect proteins.

When did photosynthesis start to put oxygen in the air?

Photosynthesis most likely started about 3.5 billion years ago as a non-oxygen-producing process.

Oxygenic photosynthesis, which until only very recently was thought to have started 150 to 550 million years old (based on fossils), is now believed to have first occurred some 1.75 billion based on new bacteria fossils from Australia and Canada. These new fossils of a cyanobacteria indicate that life evolved to use the energy of the sun to break apart molecules of water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2) to extract and release the oxygen (the O). To say this was a life-changing process is the ultimate truism (or an understatement?). It radically transformed Earth’s atmosphere and created whole new ecosystems, paving the way for the rise of aerobic life and more complex organisms.

Aphids — TMI?

There are about 1,350 species of aphids in North America but only a dozen or so are considered serious pests.

These insects have pear-shaped bodies with “exhaust pipes” called cornicles protruding from the back end of the abdomen. They are used to exude droplets of waste product that is a quick-hardening defensive fluid called cornicle wax.

When aphids hatch from overwintered eggs in the spring, they are wingless and only female. These females, after feeding, will then give birth to live young (viviparity; without mating = parthenogenetic reproduction).

Only 25 percent of all plant species will get attacked by aphids. The aster/sunflower family (Asteraceae), conifers, and the rose family (Rosaceae) provide a food stop for the highest number of aphid species.

In order to get enough nitrogen (a key component of their exoskeletons) in their diet, aphids must ingest far more sugar and liquid than they need. They excrete the excess sugar water in a form we call “honeydew.” This sticky honeydew coats plant leaves (other plants, patio tables, cars, or pretty much anything else below where the aphids are feeding). A special group of molds — sooty molds (different Ascomycete fungi, which includes many genera, the more common being Cladosporium and Alternaria) — often develop on the honeydew mess, covering the plant’s leaves (and the rest) with faintly fuzzy black growth that looks to be a plant disease. Although the mold may reduce the plant’s ability to photosynthesize, there is no existential crisis to the plant.

Some species of ants are attracted to and feed on this honeydew. Ants will protect the aphids from natural enemies (such as ladybugs, lacewings, and hover fly larvae) by fighting them off or outright killing the predators as well as removing the eggs of some. When an aphid’s food source is depleted, ants will carry them to new plants.

Ladybugs that eat powdery mildew?

It’s great that we have some very well-known allies in our gardens that help keep down the aphid populations. But few gardeners know that we have ladybugs that eat powdery mildew (another bother in the home garden). At least two genera of ladybird beetles eat the mycelia, spores, and spore-forming structures of powdery mildews. The genus Psyllobora comprises 17 species in India, Asia, North America, South America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Australia has its own group, with 14 species of fungus-eating ladybird beetles in the genus Illeis.

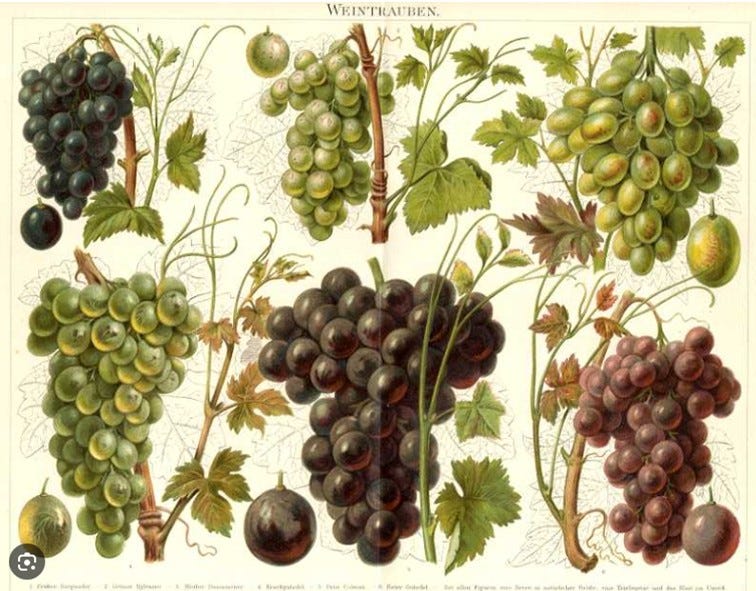

Where did grapes come from?

A study of fossilized seeds from Panama, Colombia, and Peru shows that the ancestor of the grape that gave rise to commercial grapes likely originated in the New World 60 million years ago. These ancient seeds represent the progenitor of the whole subfamily Vitoideae (which is pretty much the entirety of the family Vitaceae, the “grape” family). That subfamily includes familiar ornamentals such as Ampelopsis, Cissus, and Parthenocissus as well as the all-important genus Vitis with its few ornamental but, more importantly, edible ones with the fruits that make raisins and wine.

The genus Vitis, THE grape, originated in North America where we have a couple dozen species. One silly species, Vitis vinifera, somehow snuck over to southwestern Asia.

So where’s the mother of the family Vitaceae? At least six million years before Vitoideae became a thing, a species of plant, ended up on a piece of Gondwana that would break off, take the scenic route northeast, and crash into the Eurasian plate. Fossils of a relative of that plant, Indovitis chitaleyae, would be found in India in 2013.

Why do some vegetables get sweet after frosts?

Some vegetables convert starch into sugar (unlike sweet corn which does it, unfortunately, the other way round. And quickly, to boot!). Over the course of the growing season, these vegetables store up energy in the form of starches. As temperatures start to drop, they convert these starches (complex carbohydrates) into sugars (simple carbohydrates) and those simpler forms act as an anti-freezing agent for the plants’ cells. This conversion is a long-term process but the first good frost often signals there’s more sugar than starch.

The champion converters: beets, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, carrots, kale, rutabagas, turnips, and most leafy greens.

What plant smells like cotton candy or burnt sugar?

The Katsura tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum) produces this distinctive, sweet fragrance, due to the presence of maltol in its leaves. This scent is particularly noticeable as the leaves change color and begin to senesce in the autumn.

What’s the largest plant inflorescence?

Darn it!! I’ve addressed this question a couple times before and I still miss something! [I once said Rafflesia arnoldii has the world's largest single flower, the titan arum, Amorphophallus titanum has the largest unbranched inflorescence, and Puya raimondii has a flower spike that can make it top out at 50 feet high.]

There is a palm, Corypha umbraculifera (the talipot palm), native to eastern and southern India and Sri Lanka, that bears the most massive, most floriferous single inflorescence of any plant. It’s 20 to 26 feet long and branches up to 40 feet wide, to produce one to several million small flowers. Oddly, unlike any other palm, this inflorescence pops out of the very top of the trunk.

Here’s the mostest funnest part: The talipot palm is monocarpic. That means it flowers only once (when it is 30 to 80 years old). It takes about a year for the fruit to ripen and after the seeds of the fruit mature, the plant dies. Monocarpic plants are not common; monocarpic palms even less so, with only a handful of such species known.

Is the Ghost Plant really a mushroom “vampire?”

I saw a headline to this effect on a story posted online by a respected botanical garden. Fun to think about, but naw, Monotropa uniflora (“Ghost Pipe”) is simply a freeloader. It doesn’t suck up the “blood” of a mushroom’s mycelia. This non-photosynthesizing plant is myco-heterotrophic; that’s a plant that gathers most, if not all, of its nutrients via (not from) a host fungus. The fungus provides food and water to trees and the trees give back some excess carbohydrates from their photosynthesis process. The Monotropa takes, without a trade, the excess of that excess. “Trickle down?”

.

.

© Copyright Joe Seals, 2025

You have done it again Joe! Amazing facts!

So interesting about the new understanding about how deep roots can go. I was wondering how my peach trees could produce such juicy peaches this year, despite a dry summer when I was rarely able to give them extra water.